| Workshop 1a | |

|---|---|

| Course | Arch 200c |

| Date | 2012/08/23 |

| Learning Objectives | Introduction to architectural graphic projection, including the fundamentals of plan, section, elevation, and axonometric. This workshop guides students through the production of their first hard-line 3-view drawing and plan-oblique axonometric. After this workshop, students will be expected to have a clear understanding of fundamental techniques in orthographic projection, including drawing in plan, section, elevation, and axonometric; the procedures of producing these drawings by hand from drawing setup to producing a finished drawing; and the appropriate use of construction lines, guide lines, and drawing layers. |

| Agenda |

|

| Uses Tool(s) | Drafting Board |

Course Introduction

Welcome to 200c!

The studio will communicate and collaborate via a variety of technologies. Upon arrival on campus, we encourage you to establish a class phone list for organizational and emergency purposes. Besides the obvious use of email, the following technologies will be employed:

- Dropbox

- is a free file-sharing and syncing service. The course will be using Dropbox as a mechanism for instructors to distribute tutorial and sample files to students, and will serve as a platform for students to share files with one another. If you do not yet have a dropbox account, it is best to ask an instructor or a classmate for a 'reference', as this will increase both parties allotted storage space. For more information, see www.dropbox.com.

- Piazza

- is social Q&A platform designed to connect students with one another and with instructors. The course will be using Piazzza as a general forum for discussing class logistics and course content. For more information, see www.piazza.com/signup/berkeley

- Studiomaven

- is an experimental web-based platform for the peer-to-peer exchange of representational techniques under active development by a cohort of researchers at UC Berkeley. The course will be using Studiomaven as a mechanism for workshop instruction and as a platform for the production of student-produced tutorials. More information will be provided after the formal start of classes.

Architectural Graphic Projection

Architectural drawing is as old as the discipline itself. By some accounts, it was the formalization of architectural drawings that established architecture as a discipline distinct from the building trades. For the vast majority of its history, architectural drawing has relied heavily on techniques of graphical projection in general (understood as protocols by which images of three-dimensional objects are projected onto a planar surface), and orthographic projection in particular.

Here, we present a broad overview of architectural drawings , organized by the type of graphic projection each employs. Note in the diagram below the changing relationship between the object depicted, the image (projection) plane, and the projection rays. While these terms are often used very casually in practice, here are some helpful distinctions:

Distinctions Among Parallel Projections

- Orthographic projections

- Projection rays are parallel to one another, and perpendicular to both the image plane and a dominant plane of the object depicted.

- Axonometric projections

- Projection rays are parallel to one another, and perpendicular to the image plane - but in no specific relationship to any dominant plane of the object depicted.

- Oblique projections

- Projection rays are parallel to one another - but non-parallel with the image plane and in no specific relationship to any dominant plane of the object depicted.

Parallel vs Perspective Projections

- Parallel projections

- Projection rays are parallel to one another. Includes all drawing types listed above.

- Perspective projections

- Projection rays are converge at a "station point" representing the disembodied eye of a viewer. Includes 1, 2, 3, and 4 point perspectives.

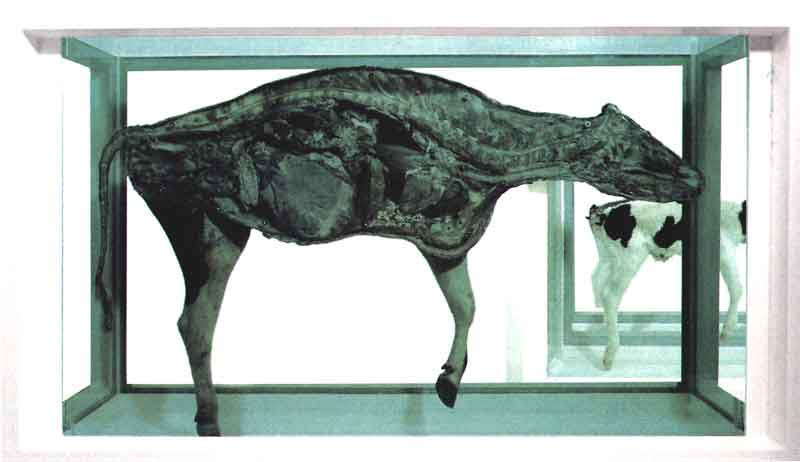

Sectional Drawings

A parallel projection drawing may be considered a "sectional" if the projection plane is positioned such that it intersects the object of interest. In architecture, sectional drawings are further categorized as either "plans" or "sections" by their relationship to the plane of the ground.

Architectural Plans

An architectural plan is a sectional drawing wherein the cut plane is positioned parallel with the ground. In most plans, the cut plane lies at a standard distance (typically 4') above the ground (a "ground plan") or above an occupiable floor (a "floor plan"). While following all the conventions of a typically architectural plan, a "site plan" isn't technically a sectional drawing at all, as the projection plane does not intersect any objects.

Plans are the most widely used graphic device in architecture. They can reveal the interrelation between the interior spaces of a design, how an occupant is able to navigate these spaces, and the relationship between a building and its surrounding context.

Architectural Sections

An architectural section is a sectional drawing wherein the projection plane is positioned intersecting the objects or space of interest, and is not parallel with the plane of the ground. Sections are most often perpendicular with the ground (vertical), but this is not a defining characteristic.

Sections are extraordinarily useful in architectural design, and can reveal the interior composition of wall systems, the interrelation of adjacent spaces, and the relationship between a building and its surrounding context.

Architectural Elevations

At first blush, an architectural elevation does not seem like a sectional drawing at all, as the projection plane does not intersect any objects of interest. Seen another way, we may define an elevation as an architectural section in which the projection plane is positioned near to, but not intersecting the objects or space of interest. Section or non-section: in either case, architectural elevations are useful for describing the exterior composition of a building, and the way in which it sits on a site or in relation to neighboring buildings.

An elevation is essentially a view of a building seen from one side as a flat representation of one façade and is the most common view used to show the external appearance of a building. Each elevation is labelled in relation to the compass direction it faces; for example, the north elevation of a building is the side that most closely faces north. Since many buildings are not simply rectangular in plan, a typical elevation may show all the parts of the building that are seen from a particular direction.

Non-Planar Sections

There are times when a sectional cannot be truly articulated using a single cut plane across the building. Particularly there will be times when a single plane will actually deceive the viewer into misunderstanding the space. When this occurs we use a technique known as non-planar sectioning which allows the cut plane to turn or jog across its cut.

The Illusion of Three Dimensions

In order to make a 2D drawing read like a 3D drawing, architects use various methods to render hand drawings.

Line Weight

Line weight is the visual lightness or darkness and width of a line. Line weights add visual interest and hierarchy to a set of drawings while maintaining clarity of representation. The quality of lines in an architectural drawing are particularly important as drawings are passed from architect to client or architect to contractor and must retain legibility to each viewer. A successful set of drawings has a consistent set of varied line weights, with typically 3 or 4 contrasting weights.

Pencil lines should be solid and uniform in width across the entire length of the line. Keep constant pressure to the paper as you draw a line from start to finish. Though the pencil lead hardness will remain mostly unchanged, the lead width will need to be altered across different drawing scales. This is changed by sharpening or dulling the pencil and altering the pressure of the pencil onto the paper.

Line Weights (from lightest/thinnest to darkest/thickest)

- Construction Lines (6H-4H, ~0.05mm - 0.1mm / 0.18 - 0.25 pt)

- The initial lines of the drawing that help to lay out the drawing on the page and create the basic geometry and guides for the rest of the drawing. These lines are to be drawn very lightly - dark enough for you to see while drawing, but delicate enough to be easily erased later. Though these lines are typically erased for construction documents, they can be kept in presentation drawings to aid in representing an architectural concept and add visual interest.

- Light Lines (4H-2H, ~0.10mm / 0.3 - 0.4 pt)

- Action lines (such as door swings), information lines (such as dimension lines and section lines), overhead lines, and fill patterns are all drawn with light lines. Though these are light lines, it's important to remember that these are still intended to be visible - do not confuse "light" with "hard to see."

- Medium Lines (F-H, ~0.2mm / 0.5 - 0.6 pt)

- Secondary objects such as doors, furniture, cabinets, and other non structural architectural features are drawn in a medium weight.

- Bold Lines (HB-B, ~0.3mm-0.4mm and above / 0.7 - 1 pt and above)

- Walls, columns, and other structural and non-structural objects that are being cut through by the sectional plane, as well as the outermost boundaries of objects in elevation or axonometric drawings, are drawn using the boldest lines.

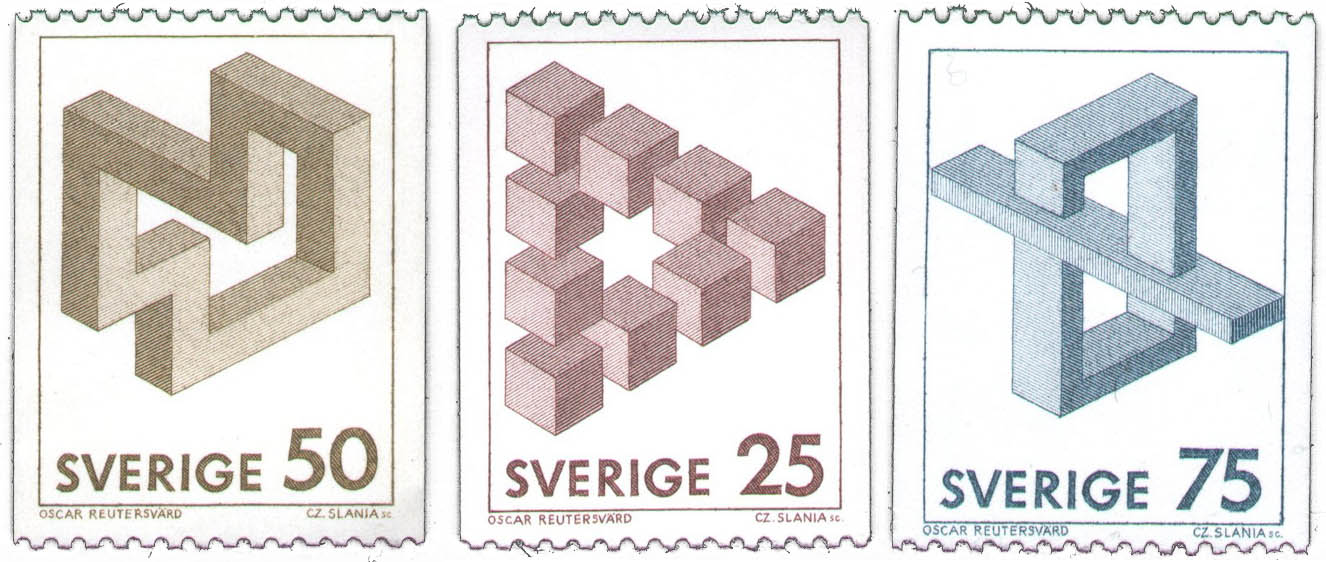

Conventions of Axonometric Drawings

In axonometric drawings we use a similar hierarchy of lineweights. In the diagram below, you can see how the differentiation of lineweights allows the drawing to read as a 3-dimensional object on a 2D plane.

- Bold Lines - Edges or boundary of the form (either edges along the outside of the object and the background as well as edges of an object protruding in space)

- Medium Lines - Planar corners (two or more surfaces touching each other and creating an edge)

- Light Lines - Surfaces lines or details (no change in form)

Line Types

- Solid Lines

- Visible objects that can be seen in plan, section, elevation, or 3D views, as well as leader lines and dimension lines

- Dashed Lines

- Hidden objects or edges of objects below or above the sectional plane, or behind other objects.

- Movement or Phantom Lines

- Used to imply movement or direction, such as the alternate position of an object that can be moved. Most helpful to differentiate between moving objects and hidden objects within a drawing. Door swings, window swings, and sliding doors are examples of when to use movement lines.

- Leader or Annotation Lines

- Connect notes or references to objects or lines in a drawing. These are solid lines that end in an arrowhead, and may be straight, angled, or curved as necessary.

- Break Lines

- Used when the extents of a drawing cannot fit into the drawing frame, or when only a portion or partial view of a design is necessary. Also used to illustrate stairs that emerge out of the sectional plane of a drawing.

- Center Lines

- Indicate the center of a plan, object, circle, arc, or another symmetrical object.

- Section Lines

- Indicates the sectional plane for a cutaway view on a drawing, as well as the viewing direction of the associated view.

- Dimension Lines

- Used to show the measurement of an object in a single direction.

Hatch, Tone, and Fill

In order to represent building materials in 2D space, architectural drawings use hatches, tones, and fills to show material differentiation. Hatches are geometric patterns with industry-standard uses for many material types, and the most common CAD software come preloaded with many hatches and the ability to create your own. Tones and other fills are used in a similar way using shades of a a single color, contrasting colors, or gradients to add visual interest to a drawing and outline geometry more clearly. Poché is an example of a fill that is commonly used to enhance the legibility of a drawing.

Texture and Entourage

Demonstration & In-Class Exercise

In class, we'll draw the orthographic representation of a set of wooden blocks. We'll create the three main architectural views of plan, section, and elevation. Our composition has three wooden blocks: two 2"x2"x2" cubes and one L-shaped block, 4" on each long side and 2" on each short side.

Before we begin, we'll cover some of the equipment you'll need and the drawing basics.

Drawing Process

Equipment Overview

- Parallel Rule

- a parallel bar with a system of pulleys and rollers that is installed onto a desk for drawing straight lines. Other tools can be used in conjunction, such as 45º, 30º-60º, and adjustable triangles, T-squares, scales, curves, and compasses.

- Architect's Scale

- Specialized triangular ruler designed for drafting and measuring architectural drawings. Each side and edge has a different set of scales to suit architectural scaled drawings, with both imperial and metric scales. Learn more about the different kinds of drawings scales here . Scales should never be used as a straightedge for drawing lines.

- Lead, Lead Holder, & Lead Pointer

- Similar to a mechanical pencil with larger leads, the lead holder and lead is the traditional architect's pencil that has a specialized sharpener to create very pointed ends and clear away debris before drawing. They are very responsive to pressure applied by the hand. Mechanical pencils and wooden pencils can also be used.

- Paper

- There are many options for paper depending on the use. Trace paper is great for sketching and conceptualizing while drawing iteratively. Vellum allows you to trace as well, but has a nicer aesthetic and can be used for presentation drawings. Strathmore and other heavier papers are meant purely for presentation.

Working from Measurements

You'll need to determine your drawing scale based upon your subject and the size of the media you are presenting on by taking the boundaries of your subject and determining how they will best fit on the page. Once the scale has been determined, use your architect's scale to draw rather than constantly converting measurements - you'll save time and have fewer errors.

Drawing in Layers

Drawing in layers is an important part of the drawing process because it allows for greater control over the final product. By starting with construction lines and soft pencil lines and gradually moving towards hard-lined drawings, architects are able to edit their drawings along the way without ruining the quality of the drawing set. Soft lines in light weights are easy to erase and recreate, but hard-lined drawings drawn with heavy weights and pressures are much more difficult to manipulate.

Begin by establishing the major guidelines of structure and/or envelope with a hard lead and soft pressure. These easily removed lines will help you frame your drawing on the page or determine if a different scale is necessary early on. From there, you'll proceed up the lineweight hierarchy, first using the light lineweight to draw everything, from action lines to fill patters to furniture to structure; then to a medium lineweight, now only drawing the detailing and structure; and finally to the heaviest of your lineweights, drawing only the cut parts of your structure and envelope.

Producing the Final Overlay

Along the way, correct and alter lines as necessary, making sure not to move on to the next heaviest lineweight until you are confident the drawing is correct. Before hardlining your drawing, be sure to look over your drawing thoroughly, since the heaviest lineweights will be difficult to remove without negatively affecting the drawing's quality. Once you've finished hardlining, erase any traces of construction lines that are unnecessary to the drawing.

The Three Basic Views

First we'll draw the plan of our composition, which will then quickly inform our elevations. We'll also be able to determine the best areas for section cut planes from our plan. Review the discussions of plans , sections , and elevations to review the conventions of these drawing types.

The Plan Oblique Axon

A plan oblique axonometric is drawn directly from a plan typically rotated 30º, 45º, 0r 60º. Then, using the parallel bar and a right angled tool such as a T-square or a triangle, verticals are drawn from the corner points and may or may not include visual foreshortening.

Homework

Students will draw a pre-chosen cafe space in plan, section, elevation, and sectional axon for our next class period.

Resources

- Francis D. K. Ching, “Architectural Graphics,” (Wiley, 2002)

- Mo Zell, “Architectural Drawing Course.” (Quatro Publishing, 2008)